The very first genetically modified food that was introduced into the market was a tomato called Flavr Savr. It was when Calgene, a California company, submitted the necessary documents for evaluation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1992. Two years later, the agency stated that the GM tomato “is as safe as tomatoes bred by conventional means”, and therefore ready for commercialization. The FDA said no special labeling requirement was necessary because research found no evidence of potential adverse health effects, and that Flavr Savr’s amount of nutrition was the same as those found in non-GMO tomatoes.

However, despite the years of work Calgene put in to develop the first GM food, Flavr Savr’s existence was shortlived. In 1997, only three years since its release, Calgene ended the production of Flavr Savr tomato. What happened?

WHAT FLAVR SAVR TOMATO WAS FOR

Tomatoes reach full maturity by around day 50. However, they naturally have a short shelf life. Typically, tomatoes can last up to 1 week in the counter. Whereas storing them in the refrigerator extends the shelf life for roughly 1 week. The short shelf life is particularly a problem during transit. As a climacteric fruit, tomatoes continue to ripen after harvest. What largely dictates the ripening process is ethylene, a colorless gas released by some fruits and vegetables. The more ethylene gas is released, the faster the produce ripens and eventually deteriorates.

Although tomatoes are moderate producers of ethylene, the rate still contributes to significant ripening. In most cases of poor post-harvest handling, tomatoes would reach the destination already soft and beginning to go off. To prevent this, growers normally harvest tomatoes unripe. And then they ripen them by artificial ripening (using ethylene). Usually, growers spray the produce with ethylene gas by the time they reach their destination. However, this method is not ideal. While it preserves the natural tomato color and maintains the fresh appearance, the flavor suffers as a result of the interrupted natural growing process. For longer travels, refrigeration is also an option to delay the ripening process. But cold temperatures have a tendency to damage the tomatoes, affecting the quality.

To address this issue, what Calgene planned was to utilize genetic engineering to produce a more shelf life-stable tomato, which would eventually be the first genetically modified food.

WHAT DID CALGENE DO?

What most people would initially think to delay ripening in tomatoes is to slow down and regulate the production of ethylene gas. But Calgene looked the other way—by interrupting the polygalacturonase (PG) activity.

The PG enzyme is plentiful in ripe tomatoes. It is largely responsible for the degradation of pectin, the acidic polysaccharide that provides strength and protection of plant cell walls. Once the pectin starts to breakdown as a result of increased PG activity, the fruit becomes softer. To prevent this in Flavr Savr, Calgene searched for a way to prevent and slow down the breakdown of pectin. And in turn, delay the ripening of the fruit. They did this by interrupting the production of PG enzyme using antisense DNA technology.

What is antisesense DNA technology?

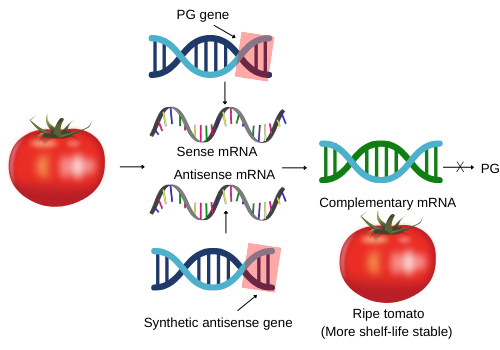

Antisense DNA technology inhibits the production of a target protein by using antisense DNA or RNA gene. In the case of Flavr Savr, the target protein is the PG enzyme.

To achieve the objective, a gene (synthetic) was inserted, which would form messenger RNA (mRNA) complementary to that produced from the gene in the tomato. (Prior to decoding of information in the DNA into proteins, mRNA translates or copies it first).

The two mRNAs would then pair and interact to create a double-stranded structure. This would not allow direct protein synthesis. With the PG activity suppressed, the pectin degradation would slow down, and the fruit would remain firm for long. Thus, the tomato would have a longer shelf life, while preserving the color and taste.

With Flavr Savr’s extended shelf life, it was straightforward to assume that it would remain in the market for a long time. But it was not the case.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Extended shelf life of tomatoes was Calgene’s primary goal. The antisense gene that they inserted in Flavr Savr worked positivity in that regard. But not to a significant extend as it did not work much on preserving the firmness of Flavr Savr, as if it was not truly a genetically modified crop. And since the antisense gene did not improve much the durability, regular production was necessary to keep pace with the increasing demand while widening the product’s reach. Another predicament Calgene faced was the inaccessibility to ideal tomato varieties (to lower the cost), forcing them to settle with other varieties. The difficulty in sourcing the most appropriate material and the production frequency ultimately cost Calgene a pricey production process—producing a pound of Flavr Savr tomatoes cost $10!

According to Calgene researcher Belinda Martineau, consumers’ reluctance to embrace genetically engineered food was not the reason Flavr Savr became a disappointing project; demand even exceeded supply during initial rollout. What led Flavr Savr to its demise was Calgene’s lack of experience in handling (from growing to transporting) tomatoes. Their mismanagement led to:

- Unrealistic production schedule

- Failure to market a better product

- Too much focused on the technical and regulatory side in product development

WHAT HAPPENED TO CALGENE?

What Calgene lacked (particularly expert plant breeders) resulted in financial difficulties. The company stopped the production of Flavr Savr for good, 3 years after it entered the market. Then Monsanto Company, an agricultural biotechnology corporation, eventually acquired Calgene. According to Monsanto’s chief tomato scientist, Harry J. Klee, Flavr Savr failed because of the minimal impact on shelf life/fruit softening, something the antisense gene had apparently failed to work on.

You might also like: Enzymatic And Non-enzymatic Browning

Although Flavr Savr, the first genetically modified food, failed, its introduction paved the way to the rapid development in the GM food segment. Today, GM foods that include soybean, corn, apples, cotton, and canola are now available in the market. At least 75 countries now import, grow and/or research GMOs, driven by the mission to mainly increase yield and reduce operation cost. The leading producers and consumers of GM foods are the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and India.