Sorbic acid as a preservative, (and its salts, sodium sorbate, potassium sorbate, and calcium sorbate) is one of the most commonly used in foods. Some of its applications include wines, cheeses, fruit juices, meat and fish products. Sorbic acid also has its same purpose in the cosmetic products. When added to personal care and cosmetics, it prevents the growth of microorganisms. Since it has a tendency to oxidize, another antimicrobial agent, citric acid, is normally combined to prevent any color change.

So, going back to sorbic acid as a food preservative, it all started in 1859. It was when August Wilhelm von Hofmann, a German chemist, first isolated sorbic acid from rowanberries’ oil by distillation. However, interest in the acid was minimal until its efficacy to inhibit the growth of microorganisms was discovered in the late 1930s. Following this was commercial production of sorbic acid in the 1940s. Demand started to grow in the 1980s, when meat companies started using sorbic acid as a nitrites alternative to prevent botulism. Nitrites are known for producing nitrosamines, which are carcinogenic.

Let’s discuss further.

Table of Contents

WHAT IS SORBIC ACID?

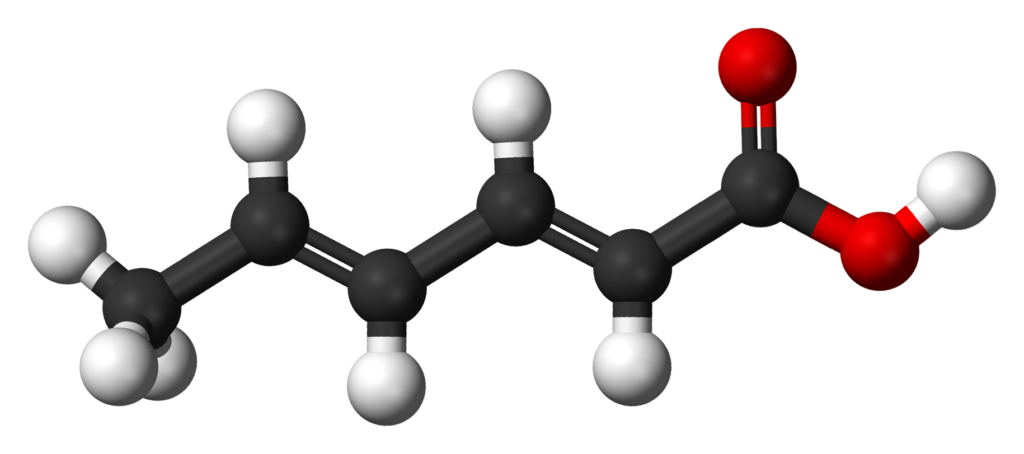

Sorbic acid is a naturally-occurring 6-chain unsaturated fatty acid. Its chemical formula is CH3(CH)4CO2H. Its E number is E200. E numbers represent the food additives that are used in the European Union. Sorbic acid appears as white powder or crystalline powder, slightly acidic and has astringent taste. In its dry state, sorbic acid is stable— even at room temperature. But it is unstable in aqueous solutions because it decomposes through oxidation. This forms products such as carbonyl compounds. The rate of oxidation varies depending on several factors. Oxidation is faster under low pH level, exposure to light, and elevated temperature. Browning in foods is a sign of sorbic acid degradation.

While sorbic acid is used by itself as a preservative, it has a low water solubility of 0.15 g/100 mL at room temperature. For this reason, sorbic acid is used for food products of low water content such as dried fruits, cheeses, and baked products. The salts (sorbates) of sorbic acid, particularly potassium sorbate (E202) and sodium sorbate (E201), are more commonly used for applications that require higher water solubility or foods in liquid form. The other salt calcium sorbate (E203) has limited uses.

METHODS OF PRODUCTION

Sorbic acid naturally occurs as the lactose, parasorbic acid in orbus aucuparia, hence the name. But commercially, sorbic acid is synthesized by several methods. These include the condensation of crotonaldehyde and acetic or malonic acid in pyridine solution. This is done by heating the mixture for several hours under steam bath. After this, the evolution of carbon dioxide stops. Then the mixture is cooled. After which, concentrated sulfuric acid is added while shaking. This separates the bulk of sorbic acid at once. Chilling the solution in an ice bath for 3 hours obtains the rest of the product. Then, filtration and washing with ice water. Next, the acid goes through recrystallization using boiling water. The purified acid separates on by standing overnight in the ice chest, and is then filtered. The yield of this procedure is about 28 to 32%. You can read more about this procedure on Organic Synthesis.

Another method of producing sorbic acid is by condensation of crotonaldehyde and ketene. This is done using a catalyst such as boron trifluoride in ether. And then converting the produced polyester into sorbic acid through saponification. This process produces 70% yield. Because of this, modified routes of this method produce the most commercially available sorbic acid globally. Check out this Google patent for more on this process.

You might also like: Sodium Benzoate (E211) As A Food Preservative

HOW SORBIC ACID AND SORBATES WORK AS A PRESERVATIVE

The antimicrobial activity of sorbic acid and its salts is attributed to their undissociated acid molecule. And therefore their efficacy is pH-dependent. The upper limit for its inhibitory activity is at 6.5 in most applications. The lower the pH, the better as a result of more undissociated sorbic acid. However, this upper limit can be raised in low water activity-solutions.

When added to water, the salts of sorbic acid (potassium sorbate, example), dissociates into sorbic acid and salt ions (potassium ions). The dissociated sorbic acid is the active antimicrobial agent. Sorbic acid works by penetrating the cell, and then changing the internal pH of the microorganism. This interrupts all the functions and metabolic activity of the microorganism and eventually eliminates the microorganism.

One clear advantage of sorbates over similar preservatives like benzoic and propionic acid is their wider range of applications. While sorbates work well even for near neutral pH environment (6.5), benzoic (4.5) and propionic acid (5.5) require lower pH levels.

APPLICATIONS

Sorbic and acid and sorbates are highly effective in inhibiting yeast and mold growth in a variety of food products, especially those of low acidity. And manufacturers prefer them safety-wise, over benzoic acid and sodium benzoate. Plus, sorbic acid works better even in less acidic conditions. Like mentioned, the optimal pH to inhibit microbial activity is just below 6.5.

The table below are the level of sorbates and their respective applications.

Food applications of sorbates

| FOOD PRODUCT | SORBATE LEVEL |

| Beverages (Fruit juices, carbonate and non-carbonated drinks, wines) | 0.02-0.10 |

| Emulsions (Salad dressings, margarine, mayonnaise) | 0.05-0.10 |

| Fruit-based products (Jams, jellies, dried fruits, concentrates, purees, syrups) | 0.02-0.25 |

| Dairy products (yogurt, sour cream, cheeses such as aged cheese, cottage cheese, processed cheese, and cheese spread) | 0.05-0.30 |

| Bakery products (pies, mixes, icings, toppings, cakes, doughnuts) | 0.03-0.30 |

| Vegetable-based products (relishes, olives, fermented vegetables, pickles, salads | 0.02-0.25 |

| Meat and fish products (salted/smoked fish, sausages) | 0.05-0.30 |

Beverages

In wines that contain residual sugar to avoid refermentation, the flavor profile is not affected at levels generally used. Some individuals taste unpleasant flavor in wine that contain a higher level of sorbate.

Cheeses

There are several ways to apply sorbic acid in food. In cheese manufacturing, sorbate is applied on the surface to prevent mycotoxin production. The cheese absorbs the preservative gradually. The rate of absorption depends on the nature of the cheese. Is it porous? How is the fat content? Typically, sorbate is completely absorbed by the cheese in about 2 weeks. In aged cheeses, the longer maturity period makes the least soluble salt, calcium sorbate ideal. Calcium sorbate is very stable against oxidation too.

In pasteurized cheese, mold may be prevented by adding not more than 0.2 % of sorbic acid by weight, potassium sorbate, sodium sorbate or any combination of these.

You might also like: What Is Citric Acid (E330) As A Food Additive

Fish products

For fish products in vacuum or modified atmosphere packaging, sorbate is added to prevent the growth of anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobic bacteria are capable of thriving despite the absence of oxygen. These microorganisms have the capability to metabolize trimethylamine oxide, the compound responsible for the “fishy” strong foul odor in fish. There are several ways sorbate is applied to fish. These include spraying, in ice, in packaging, in fat, as a powder or by immersion in sorbate solution. Commonly the fish is immersed in a solution of 0.5–2.0% sorbate and 15–20% NaCl (salt) prior to refrigeration.

Food emulsions

In food emulsions such as salad dressings, fat spreads, and butter, sorbate is often combined with benzoate for better effect. Aside from preserving the food, other benefits of this combination is reduced oxidation, free fatty acid, and thiobacbituric acid. The level of sorbate in emulsions range between 0.05-0.10%.

Vegetable based-products

Pickled and fermented vegetables already are acidic to inhibit mold growth. But adding sorbate at relatively low levels of 0.02-0.25 during fermentation makes them more shelf life stable. What makes sorbic acid more ideal is that it is not very effective against lactic acid bacteria (LABs), which are essential in fermented vegetables. For this reason, it is very effective in suppressing yeast growth without interrupting the fermentation process.

Meat and fish products

The availability of sorbic acid lessens the nitrite levels in meat, particularly in cured meat products. And it is even more effective than other preservative such as acetate and lactate against Listeria monocytogenes in cooked bologna, one study found.

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Toxicity study of sorbic acid and sorbates

Toxicity studies have revealed that sorbic acid and sorbates have low toxicity. Animal studies revealed that even tests that involved larger doses of longer time periods showed very low levels of toxicity. One study involved injection of sorbic acid at 40 mg/kg per day directly into the abdomen of male and female mice for 60 days. Results revealed no changes between controls and injected mice in survival rates, growth rates, or appetite.

These studies therefore devoid the preservatives of carcinogenic activity. The low levels of toxicity levels are attributed to the fact that sorbic acid, similar to other fatty acids, is metabolized very quickly. A few cases of non-immunological contact urticaria and pseudo-allergy have been reported in humans. However, these incidences are very few for accurate assessment.

At high concentrations and temperature, sorbic acid may react with nitrite in meat to produce mutagens. But these mutagenic products are not observable under normal levels, even in curing brines.

You might also like: Umami and Everything You Need To Know About MSG

Sorbic acid to lower the nitrite levels in cured meats

Consumers are so wary of cured meat products such as bacon, hot dogs, and salami because of their components —especially nitrates and nitrites. Nitrates when added to these products get converted into nitrites, the active antimicrobial agent. They are especially effective against the potentially fatal illness botulism and other foodborne diseases.

Color enhancing is another function of nitrates/nitrites in curing of meats. When applied to meat, the nitric oxide from sodium nitrite reacts and binds to metmyoglobin as well as myoglobin. This interaction results in a bright red pigment called nitroslymyoglobin. When the meat is subsequently heated, chemical reactions occur which leads to the formation of nitrosylhemochrome, the pink pigment responsible for the appealing appearance of cured meat products.

Nitrates/nitrites maybe are key ingredients in cured meats. However, what affect their market is their reputation of producing nitrosamines, which are believed to be strong carcinogenic byproducts.

To prevent high amounts of nitrites, sorbic acid is combined with ascorbic acid to reduce mutagenicity and the formation of nitrosamines. The presence of sorbic acid and ascorbic instead forms nonmutagenic compound, 1-nitro-2-methyl-4-aminopyrrole.

When used as a preservative, sorbic acid and sorbates are used at 0.05 to 0.30 % for meat products such as sausages. The same levels also apply for fish (smoked or salted).

REGULATIONS

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has listed sorbic acid as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) in accordance with good manufacturing practice.

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) has listed sorbic acid as an antimicrobial preservative and fungistatic agent. The acceptable recommended daily intake of sorbic acid is up to 25 mg/kg of body weight.

In Europe, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has listed sorbic acid in Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 as an authorized food additive under the category “Additives other than colours and sweeteners.”.

Other references:

J. H. Subramanian, L. D. Kagliwal, R. S. Singhal (2014). Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition). Academic Press

L.V. Thomas, J. Delves-Broughton (2014). Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition). Academic Press

J.A. Maga, A. T. Tu (1995). Food Additive Toxicology. New York : M. Dekker